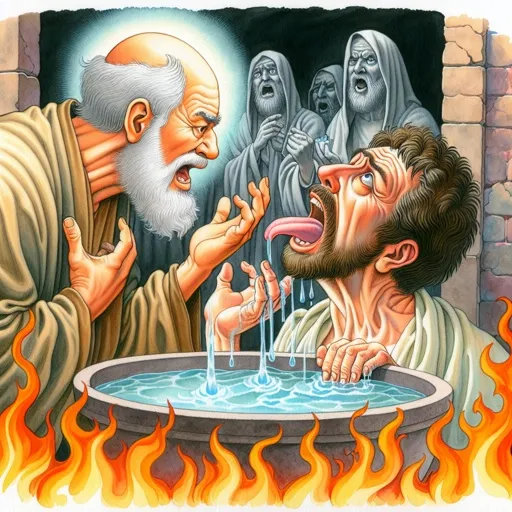

'The Rich Man & Lazarus' - Is it about Hell?

Is it a Literal Depiction of Hell or a Parable/Story with a Lesson?

2025-12-10 by Steve Forkin

For many centuries, most of those commenting on the parable of the rich man and Lazarus have assumed that the place Lazarus is taken after he dies, ‘Abraham’s bosom,’ is in heaven, but this has not always been the case.(Ed Christian)

For many centuries, most of those commenting on the parable of the rich man and Lazarus have assumed that the place Lazarus is taken after he dies, ‘Abraham’s bosom,’ is in heaven, but this has not always been the case (Ed Christian). 1

One of the cardinal rules in interpreting a biblical text is its context. It is helpful to review the context of the whole chapter of Luke’s gospel that contains the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus. Verses 1 to 8 tell the story of a dishonest business manager. In verses, 9 to 13 Jesus applies this story to his audience. In verses 14 and 15, the Pharisees who were lovers of money demonstrate this by their reaction. In verses, 16 to 18 Jesus holds up John the Baptist as an example of faithfulness. The reference to divorce in verse 18 seems, at first, a little out of place. It is helpful to remember John’s scathing rebukes of Herod, who was a ruler captured by greed and a adulterous relationship. With this in mind, the connection to greed in the context of the whole chapter seems to come more clearly into view. The history of Herod and John the Baptist is well demonstrated by Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews. 2

Jesus’s statement it is easier for heaven and earth to pass away than for one dot of the Law to become void (Luke 16:17), makes sense of the connection to verse 18. John was unwilling to forgive Herod for marrying his brother’s wife in violation of Leviticus 20:10. John is juxtaposed with Herod here. John faithfully served God and was true to his word. It cost him his life.

The parable in the opening of chapter sixteen has an overall message that concludes with the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus. Taken together, the parable and these sayings serve as a summons and challenge to discipleship, which includes the right attitude towards wealth. 6 The reader is encouraged not to be a servant to money or greed, regardless of how much of it he possesses. In this section, it is important to note that Luke makes a categorical statement about the Pharisees and their attitude to wealth: The Pharisees, who were lovers of money (Luke 16:14a).

Jesus’s stern rebuke indicates that the Pharisees likely held the view that their advanced status and wealth were a sign of their superior relationship to God.

In the final part of chapter 16, Jesus tells us the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus. The context of the chapter leading up to this story, as just demonstrated, is greed and the love of money. The context warrants that this story itself is likely a continuation of, the same topic. There is a point of contention between commentators of this story.

The contention is whether it is a parable, a story, or whether it is an actual account of what happens to people after they die. I’d like to suggest that the passage about the Rich Man and Lazarus is based on a folk tale. Jesus’s audience was familiar with the tale and likely to understand the message Jesus drew from it. The message is inline with the context of the rest of the chapter.

Given the existence of several such stories in the common knowledge of that period and the low level of literacy in the audience of Jesus, it makes sense for Jesus to draw on such knowledge to give some helpful connection to the message he aims to tell.

Hultgren confirms:

Stories of the fate of the rich and the poor in the afterlife abound in various traditions and literature. A story of this kind is expressed in an Egyptian tale that was probably older than the time of Jesus, and there are several versions of this kind in rabbinic literature (all dated later than the NT). Yet the parable is not a replica of any. While it is related to common folklore, it is a creation in it’s own right. 8

Some in favor of it being an actual account, claim that it is not introduced as a parable, like most of Jesus’s parables are. The use of the word ‘certain’ concerning the rich man in verse 19 lends some credence to the actuality of the story. It is not helpful to this claim that this is translated so only in the KJV, as opposed to most modern translations that just use the indefinite ‘a’.

It is also not helpful for this argument that several other parables use this same word ‘certain’ in the KJV such as the parable of the talents in Matthew 18.

A further argument in favor of the actual account interpretation is that the proper name Lazarus is used, which is not the usual pattern in parables “Some look upon it as a simple parable; but as the name Lazarus occurs in it, I rather consider it to be of an actual fact.” 9 A reasonable objection to this argument could be raised from Balaam’s oracles in Numbers 23 and 24. These oracles are generally regarded as poetic oracles with both a direct and foreshadowing of the Christ to come, and yet they have several proper names in them. 10

Usually, the parables of Jesus contain some kind of a figure-of-speech with a comparison made between something this-worldly and something of importance in God’s kingdom. Hultgren categorizes the parables of Jesus into two distinct types. The story of the rich man and Lazarus seems to fit his definition of Narrative parables: the comparisons made include narration; these parables typically have a ‘once upon a time’ quality about them and the particularity of stories set in the past. 11 This is a strong inference in favor of the parable/story view, regardless of whether Jesus actually drew on other commonly known sources or not. The story has several comparisons, firstly the comparison of the two people in this life, then the comparison of their outcome in the afterlife, and finally the comparison of this life with the afterlife.

The English word ‘parable’ is a loanword from the Greek word ‘parabole’, and like it’s Greek antecedent its basic and primary meaning is a ‘comparison’. By means of parables Jesus — and others before and after him — carried on instruction by making comparisons between eternal, transcendental realities and that which was familiar to the common human experience of his day. 12

The story of the Rich Man and Lazarus has two sections. A reversal of fortunes in the afterlife, and a plea by the rich man to have his brothers rescued from suffering the same fate, by a miracle. In this sense, it has a common parabolic flow.

Ed Christian likewise says that Jesus regularly drew on audience knowledge of subjects like agriculture and travel. It is therefore no unreasonable to suggest that Jesus drew on a known folk-tale to help his audience understand his message. It would be appropriate for him, in telling a parable, to draw on the folk beliefs of his listeners, just as he drew on their knowledge of agriculture, travel and master-servant relationships. 13

It is interesting to note that John Calvin, who was persuaded of the literal account view of this passage, was not dogmatic as to the genre of the passage as long as one comprehended its main message. I rather consider it to be of an actual fact. But that is of little consequence, provided that the reader comprehends the doctrine which it contains. 14

Calvin jumps to the conclusion that the torments mentioned in this passage are everlasting torments, “On the other hand, to be sentenced to everlasting torments is a dreadful thing, for avoiding which a hundred lives, if it were possible, ought to be employed.” 15 It must be stated here that this passage does not have anything to say about both the judgment of the sinner or the duration of the penalty. Calvin’s conclusion Let it be reckoned enough that the inconceivable vengeance of God, which awaits the ungodly, is communicated to us in an obscure manner, so far as is necessary to strike terror into our minds, 16 seems entirely in line with the message this passage aims to convey.

The pseudepigrapha, i.e. extra-biblical religious texts in Jewish tradition written both before and after the life of Jesus, reveal that speculation about the afterlife was rampant, 17 in Jesus’s day. This puts a responsibility on the exegete to take great care when attempting to reconstruct Jesus’s view of the afterlife from these documents. In respect of final authority, it seems safest to draw any conclusions that Jesus held, in this respect, is from the OT and his own words.

When this story is broken down into its constituent parts, several objections to the literal account of the afterlife-view, come to light. Hultgren suggests that the poor man went to heaven. The poor man is carried away by angels, escorted into heaven with their aid. 18 In his footnotes on this comment Hultgren references a Rabbinic Commentary, 1 Enoch 22:1-14, and 4 Macc 13:17, in support of his view. Christian raises a valid objection, Nothing in the text places righteous ones in heaven. This is merely Hultgren’s assumption based on his theological presupposition. 19

Hultgren also compares the poor man going to heaven with God taking Enoch, in the book of Genesis. The scene recalls the taking of Enoch to heaven by God (Gen 5:24). 20 Enoch was indeed taken by God. However, that passage is far too short to give a detailed picture what occurred and it seems quite a far stretch to use this as evidence in support of the view that being carried to Abraham’s side is the same thing as being taken to heaven.

Whilst there appears to be a consensus in favor of Hultgren’s view, I would like to suggest that the textual support for this view is not as strong as he contends. Verse 22 simply says, the poor man was carried to Abraham’s side (Lk 16:22).

Christian demonstrates from one of the earliest church Fathers in the second century that Abraham’s side mentioned in this parable is not heaven but rather: Abraham’s bosom where the righteous now dwell is not heaven but ‘Hades’. What we see is an imaginative, Hellenized, literalized, version of the more abstract OT metaphorical concept called ‘Sheol’… this does tell us that two centuries after Christ, this is what the most important theologian and the most prolific religious writer of his day thought Christ meant when he used the term. 22

Both the rich man and Lazarus appear to end up in the same place. Whilst there is a great divide between them between us and you, a great chasm has been fixed (Luke 16:26), the fact that they can see and call out to each other he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham afar off and Lazarus at his side. And he called out (Luke 16:23-24), are strong indicators to the reader to recognize that they are in the same place.

The NIV has the rich man looking up he looked up (Luke 16:23) and this has lead some to conclude that Lazarus is in heaven while the Rich man is in ‘Hades’. Various other translations such as the ESV and RSV render this phrase as he lifted up his eyes (Luke 16:23). 26

As Ed demonstrates, this phrase is just an idiomatic expression that usually means ‘looking’, 27 in other words, instead of looking down which is likely in the Rich man’s circumstances, he looks out over the horizon. The idiom suggests an eye movement from looking down to looking out or looking at. 28 Nothing in this phrase demands the view that Lazarus is in heaven i.e. in a completely different place.

Hippolytus, one of the most influential church fathers writing in the second century, agreed that ‘Hades’ was the place where all the dead, both the righteous and the unrighteous, are detained. He wrote writing in Greek to Greeks, wrote that Hades is where ‘the souls of the righteous and the unrighteous are detained.’ 29

The general view of the Old Testament, regarding the location of the dead, is a resting place. It is called ‘Sheol’ in Hebrew. The Greek translation of the Old Testament, in wide use in the first century, translated the Hebrew word ‘Sheol’ as ‘Hades’ in Greek. By the time the LXX ( = Septuagint) was produced, ‘Hades’ was seen as the best translation of ‘Sheol’. 30

This New Testament uses three different words translated into English as hell. One of these is ‘Hades’ and this is the place referenced in the story under review. It is therefore relevant to compare what the Old Testament defines as ‘Sheol’.

In the OT, when sheol, the place of the dead, is mentioned, few details are given. David’s understanding of death is revealed in Ps 6:5: For in death there is no remembrance of you, he says to God, then asks, in Sheol who can give you praise? The unnamed author of Ps 115:17 has similar views: The dead do not praise the Lord, nor do any that go down into silence. — Job, immersed in his suffering, says to his friends, Mortals lie down and do not rise again; until the heavens are no more, they will not awake or be roused out of their sleep (Job 14:12).

Important to note here is the categorical statement that mortals do not rise again until the heavens are no more. Whilst there is a range of passages in the Old Testament that have the dead speak and stare or even greet a newly dead king (Isa 14:9-11), one must remember that although much of the OT is meant to be read literally when we read poetry we are in the land of metaphor. 33

The Old Testament frequently uses the terms ‘cut off’ (‘karet’ in Hebrew) in a negative sense of people who have broken their covenant relationship with God. Those who have been faithful are frequently said to be ‘gathered to his people’. Christian makes a good case that both of these terms are metaphors for resting and awaiting, either the judgment to come or eternal bliss. This concurs well with Daniel’s description of the future judgment: And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt (Dan 12:2).

By this light we see that in Jesus’s parable, the rich man has been ‘cut off’ from ‘Father Abraham’, and so evidently from the rest of the ‘fathers’. They are all in ‘hades’, but the rich man is ‘tormented’, while Lazarus is ‘comforted’. The rich man has suffered the penalty of ‘karet’ and between him and his fathers is a chasm he cannot cross over. Meanwhile Lazarus though a beggar in life is with the ‘fathers’ in death awaiting resurrection. 35

The Old Testament prophets broadly declare a final day of reckoning and of judgment at the culmination of time. The book of Acts chapter two details the apostle Peter’s first sermon, and in this sermon, Peter quotes directly from Psalm chapter 16. Peter draws a connection between Christ’s death and resurrection, and the death of David. Peter states God raised him up, loosening the pangs of death because it was not possible for him to be held by it. . . For you will not abandon my soul to ‘Hades’ (Acts 2:24, 27), including a direct quotation from Psalm 16. He then explains how David had spoken prophetically about Jesus. Death could not hold Christ given that he was without sin.

The important connection here is the use of the word ‘Hades’ in connection with both David and Jesus. It is a strong argument in favor of the belief that both the Old and New Testaments agree that all people initially go to the same place when they die and that this is neither the ‘final heaven’ nor the ‘final hell’. This view comports well with the idea of ‘soul sleep’ as referenced by the book of Daniel chapter 12. It is noteworthy that Martin Luther, arguably the initiator of the protestant reformation, held to ‘soul sleep’.

Anglican priest Francis Blackburn writing in 1765 on the controversy over the intermediate state and the state of departed souls writes concerning Martin Luther: Luther’s sleeping man was conscious of nothing, and in this very circumstance he places the difference between the sleep of a living man, and the sleep of a departed soul. Here he makes the sleep of the living man, and the sleep of a departed soul to correspond throughout. 37

The view, of the actual condition of each person, when one dies, i.e. whether one goes to an ‘intermediate state’ or sleeps does necessitate a literal view of the passage in question. In this paper, the author is merely aiming to determine the correct interpretation of this passage in Luke, and soul sleep does not need to be true in order to deny a literal interpretation of this passage, it just helps the non-literal view.

A literal view of this passage in Luke would demand that one accepts that the dead are somehow transported to a place called ‘Hades’, and then tormented there. This, without having been judged first, considering that this passage indicates that the final judgment has not yet occurred and that in no other place in both the Old and New Testaments are two final judgments referenced. The dead are then transported a second time to be brought before God at the final judgment only to be subsequently thrown into a second place place of torment, this time in the traditional view, forever. This idea of two different periods of punishment one before the judgment and one after it, is at odds with the overall Biblical story. It is without precedence in scripture to punish without a judgment or verdict, and also to punish twice for the same thing.

The account of Jesus raising the real Lazarus from the dead confirms common beliefs about the afterlife in Jesus day. Martha said to him, ‘I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day’ (John 11:24).

Therefore, the absurdity of taking this passage literally becomes obvious. Luke 16:24 has the Rich man calling out to Abraham for mercy. When taken as a literal account, this indicates that Abraham has some type of mediator role. This kind of role is not found in either the Old or New Testaments.

Jesus ascribes the role of mediator to himself only: I am the way, the truth and the life, no one comes to the father except through me (John 14:6). Ascribing such a role to Abraham, might lend some credibility to Roman Catholic views of praying to saints, but it causes consistency issues with the clear statement of Jesus.

The idea of Abraham’s bosom is not strictly mentioned anywhere in the Old Testament, neither are there any passages recording literal conversations between the dead in ‘Hades’ or ‘Sheol’, passages of poetic genre excepted.

Finally this story does not mention anything concrete about the spiritual state of either the rich man or Lazarus. The rich man is not portrayed as particularly wicked; he is simply not attentive to the situation (the poor many nearby). Nor is it said that Lazarus was particularly good; he simply has no help by God alone. 40

There are some indicators about the behavior of both the rich man and Lazarus, but far too little to be certain about their eternal state. Overall the literal account view appears to have some insurmountable exegetical hurdles. Those who view it as an actual account, must answer the objections raised by a detailed comparison with the general view of the after-life as depicted in both the Old and New Testaments.

All these facts, are strong indicators that this passage called the rich man and Lazarus is a story or parable based on a known folk-tale that first century Jews would have been able to comprehend and associate with. The message is about regard for economic standing and a call to generosity.

When considering the context that this passage is in, it is an exhortation to see the conditions of those who suffer and to see them as persons created in the image of God. 41 Finally, the comparisons between this life and the afterlife, the ‘fixed gulf’ between those who have done well and those who have not, and Jesus words If they do not hear Moses and the Prophets neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead, 42 should be cause for some serious reflection.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ed Christian, The Rich Man and Lazarus, Abraham’s Bosom and the Biblical Penalty Karet (“Cut Off”), Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 61.3 - 2018.

Flavius Josephus, Project Gutenberg, The Antiquity of the Jews, https://gutenberg.org/files/2848/2848-h/2848-h.htm#link182HCH0005, 2017.

Arland Hultgren, The Parables of Jesus, A Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1998.

John Calvin, Calvin’s Commentary on the Bible, “Commentary on Luke 16”, https://studylight.org/commentaries/eng/cal/luke-16.html?print=yes, 2021

Reformation Study Bible, “Numbers”, (Sanford, FL: Reformation Trust Publishing, 2017)

Francis Blackbourne, A Short Historical View of the Controversy Concerning an Intermediate State and the Separate Existence of the Soul Between Death and the General Resurrection, Creative Media Partners LLC, 2018.

1 Ed Christian, The Rich Man and Lazarus, Abraham’s Bosom, and the Biblical Penalty Karet (“Cut Off”), (Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 61/3, 2018), p. 513.

2 Flavius Josephus Project Gutenberg The Antiquity of the Jews, Book 18, “Chapter 5”, August 9, 2017, https://gutenberg.org/files/2848/2848-h/2848-h.html#link182HCH0005, (February, 1, 2021).

3 Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture is from the English Standard Version (Crossway, Copyright c 2001).

4 Arland J Hultgren, The Parables of Jesus, A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 1998), p. 147.

5 Hultgren, p. 147

6 Ibid., p. 152.

8 Hultgren, p. 11.

9 John Calvin, Calvin’s Commentary on the Bible, “Commentary on Luke 16”, https://studylight.org/commentaries/eng/cal/luke-16.html?print=yes, (January 10, 2021).

10 Reformation Study Bible, “Numbers” (Sanford, FL: Reformation Trust Publishing, 2017), p. 219.

11 Hultgren, p. 3.

12 Hultgren, p. 2.

13 Christian, p. 515.

14 Calvin, (January 10, 2021).

15 Calvin, (January 10, 2021).

16 Ibid.

17 Christian, p. 515.

18 Hultgren, p. 113

19 Christian, p. 516.

20 Hultgren, p. 113

22 Christian, p. 518.

27 Christian, p. 519.

29 Christian, p. 517.

30 Ibid., p. 515.

31 Ibid., p. 514.

33 Christian, p. 515.

35 Christian, p. 523.

37 Francis Blackbourne, A Short Historical View of the Controversy Concerning an Intermediate State and the Separate Existence of the Soul Between Death and the General Resurrection (Creative Media Partners LLC, 2018), p. 120.

40 Hultgren, p. 112

41 Ibid., p. 116